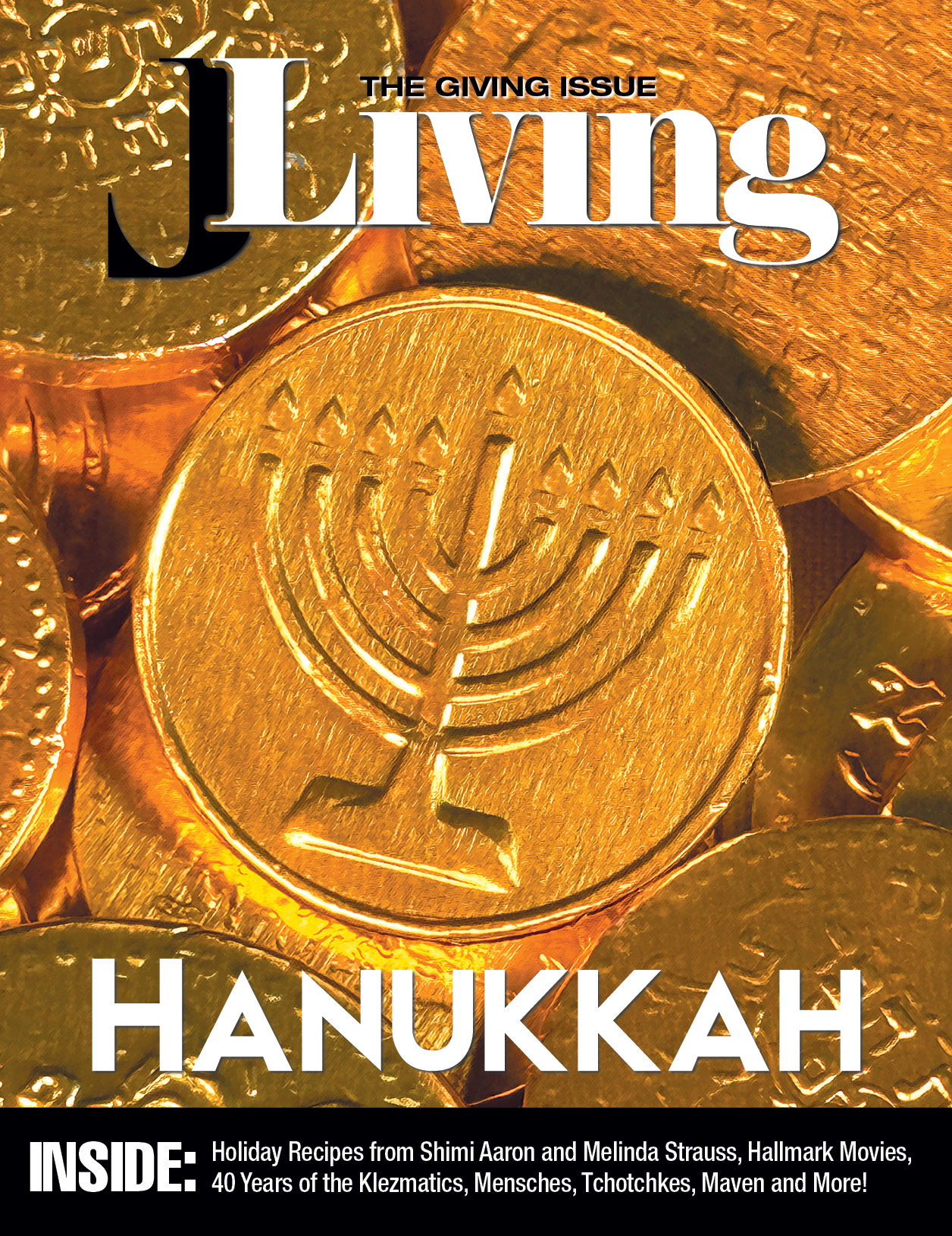

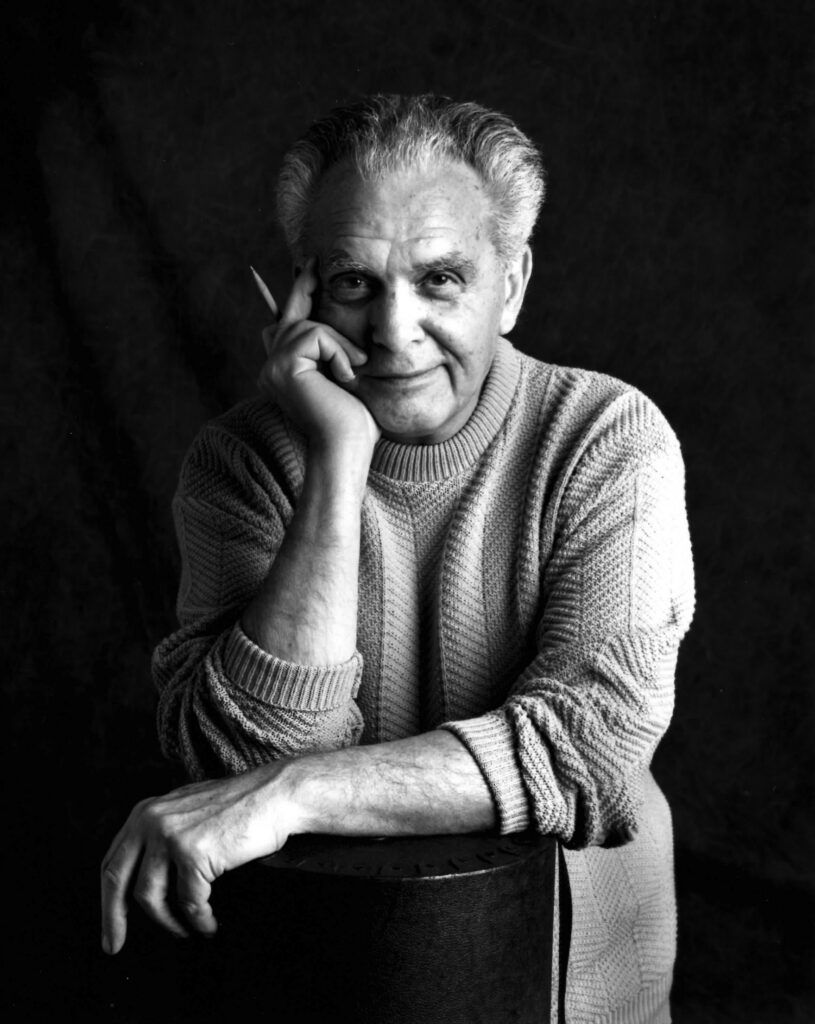

Jack Kirby

“I don’t like bullies; I don’t care where they’re from.”

— Captain America

When I was around 8 years old, I loved the X-Men Marvel comics, action figures and TV series. So, of course, I instructed my mom that my name would no longer be Casey — it was now Wolverine.

One day, on an outing to T.J. Maxx, I decided to hide in a rack of clothes. My mom was terrified, “Casey! Casey! Where are you?” She thought I had been kidnapped! After a few minutes, I finally jumped out and said, “Mom, I told you my name is Wolverine.” She gave me a potch on my tuchus and told me she was never calling me Wolverine again. That was Jack Kirby’s influence on me.

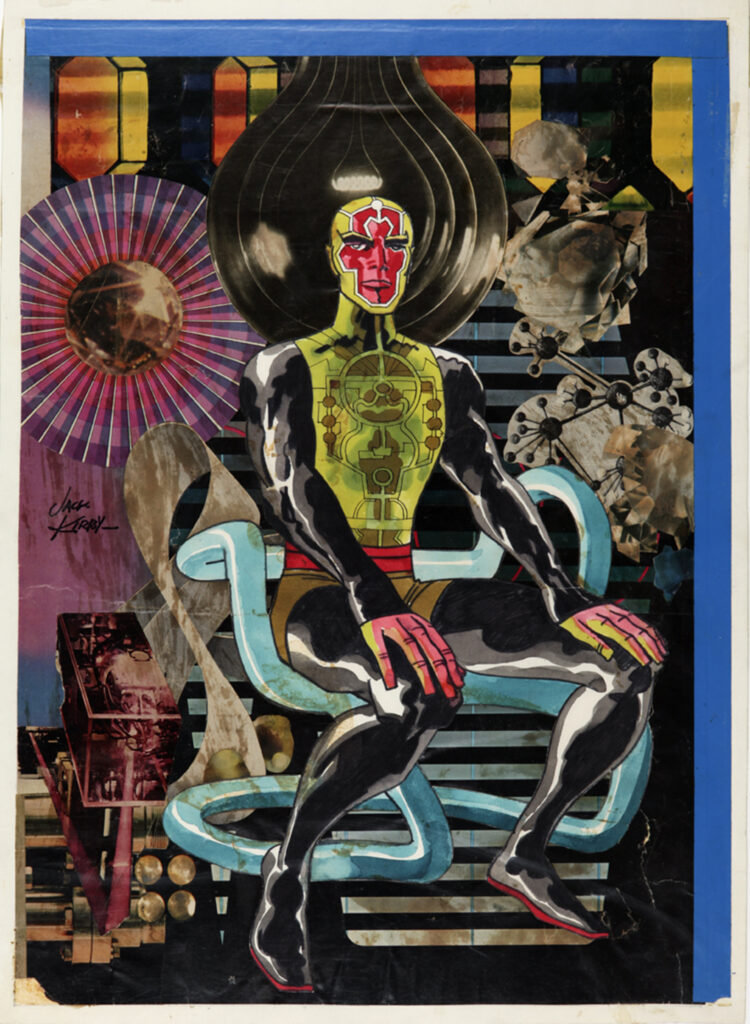

Jack Kirby is the iconic comic book artist who created or drew or had some kind of hand in the most recognizable 20th century champions of justice — superheroes like Captain America, Hulk, Black Panther, Fantastic Four, Dr. Doom, Thor and the X-Men. Kirby is currently having a retrospective exhibit at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles.

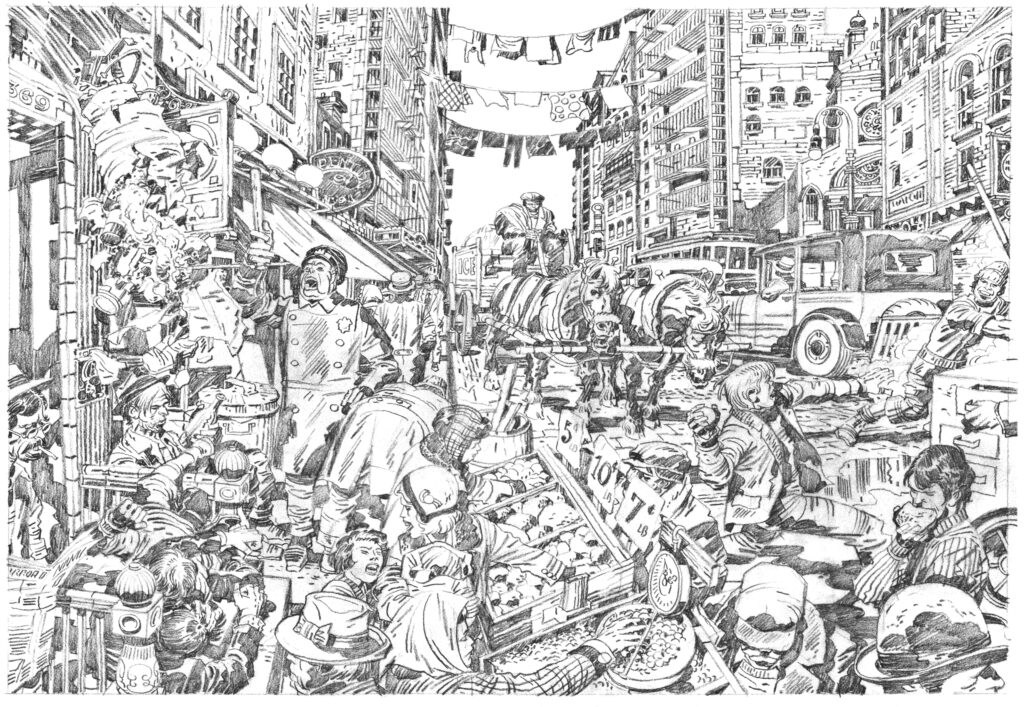

Kirby was born Jacob Kurtzberg in 1917 and grew up as a first-generation Jewish New Yorker in the Lower East Side. Not necessarily religious or secular, the Kirbys fell into the most recognizable category of a little bit of tradition and a lotta bit of assimilation. This formative experience alongside a milieu of immigrants and ethnicities in New York would define much of Kirby’s art and politics.

In Kirby’s adolescence, comics were a completely nascent art form. They grew out of the pulp publishing industry, where Tarzan and Buck Rogers came into being. “Comics were the bottom of the barrel, completely disposable entertainment, and were produced very quickly,” said Patrick A. Reed, co-curator of the Skirball retrospective. “It was commerce, first and foremost.”

According to Reed, this was the first time that “kids were targeted as their own market.” But once Superman arrived on the scene in 1938 as the first real superhero, the industry grew like wildfire, and anti-union publishers utilized assembly lines and sweatshop studios to keep up with the skyrocketing demand and avalanche of profits.

Interestingly enough, the business of comics hasn’t changed much since the early days. The most surprising aspect to learn is that comic book artists do not receive any residuals because it is all work-for-hire contracts. Some of the greatest artists and their creations have made publishers, movie studios and gaming companies billions of dollars, yet they do not receive any profit sharing, which includes Jack Kirby, as noted by Comics Lawyer in its article, “Jack Kirby and Work Made for Hire.” Since Kirby received a flat fee, he did not own any of his characters.

Reed emphasized that politics has always been a huge part of comic book storytelling. “It’s a complete and utter fallacy to claim that comics were never not political,” he said. “Superman was created from two Jewish men from Cleveland, and the first issues confronted corrupt politicians.”

Reed went on to explain that the first-ever issue of Captain America, co-created by Kirby and Joe Simon, depicted the eponymous superhero socking Hitler in the jaw — an entire year before America entered the war. In fact, Kirby’s own story with Nazis didn’t start and end there.

Kirby’s office was a block from Madison Square Garden, where in 1939, the largest American Nazi rally was held. Reed offered that the 23-year-old artist was “quite conscious of the looming danger of fascism.” Timely Comics, the publisher of Captain America, got a bit of flak from the German American Bund when a group of American Nazis showed up at the office and asked, “Are the Captain America guys there?”

Kirby might’ve been 5 feet 2 inches, but he was no pushover. According to Reed, the apocryphal reply from Kirby to the receptionist was, “Keep them there. I’ll be right down.” By the time Kirby reached the bottom floor, the fascists were out of sight.

Kirby’s Nazi experience didn’t remain stateside. He landed on the beaches of Normandy just after D-Day and eventually served as an army scout, providing reconnaissance sketches and maps of towns. He was an artist as a civilian and as a soldier.

Skirball Museum Director Sheri Bernstein sees Kirby’s creations couched in the framework of the great tradition of Jewish storytelling: “There were so many Jewish people involved in the early years of comics because there were many fields where Jews were not welcome,” Bernstein said. “The comic book industry was just arising, and there were not the same bars to entry.”

As Bernstein led me through the exhibit’s colorful, eye-popping maze, she pointed out one of her personal favorite objects — Kirby’s hand-drawn family Hanukkah card, with an image of The Thing from the Fantastic 4 reading the siddur. Kirby stayed active in the Jewish community throughout his life. He and his wife, Roz, would volunteer at their temple and help with bake sales.

Moving through the exhibit is like moving through the 20th century, with the 40s to the 60s just a few steps away. It was fascinating to view the original rendering of T’Challa, the main character in Black Panther, which is now a major motion picture series made famous by Chadwick Boseman. Through Black Panther, the first Black superhero in an American comic, Bernstein explained that Kirby “took all of the racist stereotypes of Africa and turned them on their head.” He wondered what it would look like if this were the “most technologically advanced society ever.”

While Kirby’s art was some of the most spectacular pieces I’ve ever observed in person, I realized that I have rarely, if ever, seen comic book art in museums. Bernstein, who received her graduate degree in art history from Harvard University, noted that comics were never found in her coursework since it was considered “lesser art.”

Perhaps that has changed, she said, but there are “gatekeepers” who often define a hierarchy of fine art vs. commercial art. There is a similarity to the way other modern art forms like jazz and hip-hop, created by Black Americans, have been derided as a lower rung of music before reaching global influence.

As we reached the final leg of the exhibit, we passed by some patrons who were gawking at the art. I asked museum visitor Anthony Ruiz what brought him to the Kirby retrospective. “Big Jack Kirby fan,” he said. “Always loved his inking and design. I used to make comics when I was a kid. As I got older, I realized that a lot of my drawings were based on his style.”

If you’re looking for an exciting and unique art exhibit for adults and kids alike, head to the Skirball to experience the story of Jack Kirby and 20th Century America. Open until March 2026.