Mishegoss – Matzah Madness

In the first month, from the fourteenth day of the month at evening, you shall eat unleavened bread — Exodus 12:18

What Is Shmura Matzah?

Shmura matzah represents the highest level of tradition and stringency in fulfilling the mitzvah of eating matzah on Passover. The word “shmura” means “guarded,” referring to the meticulous care taken to prevent any chance of leavening. While regular matzah is typically supervised only during the baking process, shmura matzah is watched from the moment the wheat is harvested to ensure it never comes into contact with moisture, which could cause fermentation. This extra level of supervision makes shmura matzah the preferred choice for the Seder, as many consider it the closest version to what our ancestors ate when they left Egypt.

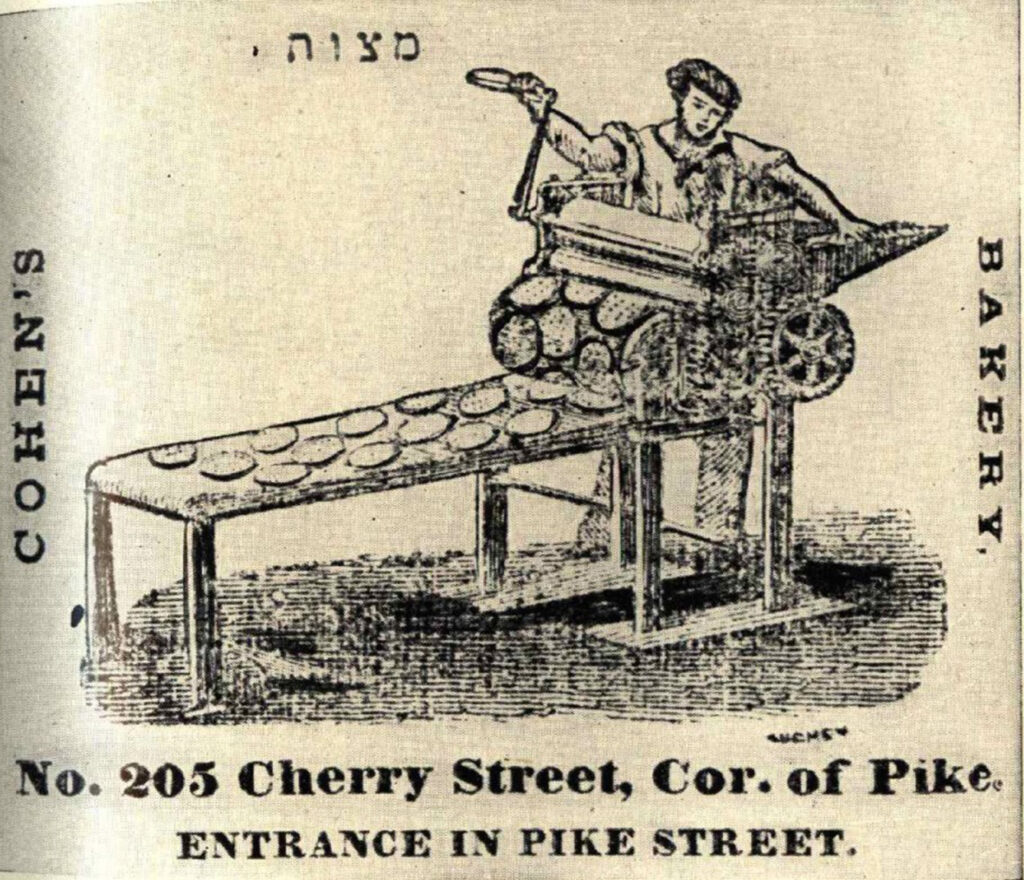

The Invention of Machine-Made Matzah

In 1838, French Jew Isaac Singer revolutionized matzah baking by inventing the first machine for its production. Unlike traditional kneading, Singer’s machine rolled the dough, significantly reducing prep time and increasing efficiency. However, this innovation sparked heated debates across Europe, as rabbis and scholars questioned whether machine-made matzah met the strict halachic (Jewish legal) standards for Passover.

In the 1880s, Dov Behr Manischewitz emigrated to Cincinnati and expanded upon Singer’s invention, incorporating a baking element into the machine. Manischewitz, a pioneer in modern matzah production, registered over 50 patents for his innovations. One of his most notable contributions was making matzah square — a shape that streamlined both manufacturing and packaging.

Today, while we have grown accustomed to square matzah, the traditional, handmade variety remains round. Ultimately, both shapes can meet the requirements for Passover, ensuring that Jews around the world can observe the holiday in a way that balances tradition and modern convenience.

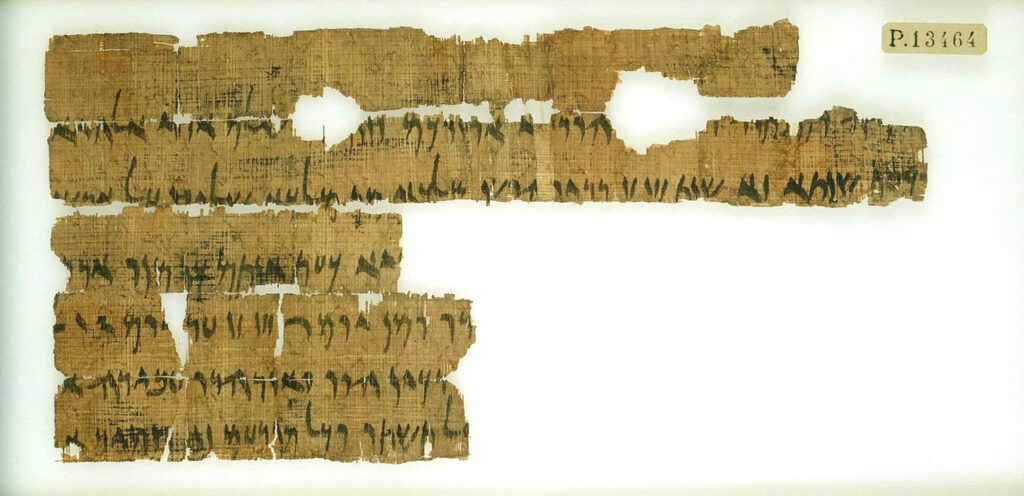

The ‘Passover Letter’ – A Glimpse into Ancient Jewish Traditions

In 1907, archaeologists discovered a collection of ancient papyri on Elephantine Island in Egypt, offering rare insights into the life, customs and religious practices of the Jewish community that once thrived there. Among these documents is the Passover Letter, dated to 419 BCE, which is believed to contain the earliest extrabiblical reference to Passover rituals.

The letter, written by Hananiah to the Judean garrison in Elephantine and its leader Jedaniah, does not explicitly mention “Passover” by name. However, it instructs the community to refrain from eating leavened bread from the 14th of Nissan at sunset until the 21st and to observe rest days on the 15th and 21st — practices that align with later Passover traditions.

Scholars have long debated the letter’s purpose. Some suggest it addressed questions about the festival’s observance during a leap year, military furloughs or the introduction of the Festival of Matzah following the first night of Passover.

However, a new theory proposed by Dr. Gad Barnea of Haifa University challenges our traditional interpretations. Barnea suggests that the letter reflects influence from Zoroastrian rituals, potentially indicating that early Passover customs evolved through a fusion of Canaanite, Zoroastrian, and even Greek traditions. If true, this theory would reshape our understanding of Passover, revealing it as a product of cultural exchange rather than a strictly independent development. As new research emerges, the Passover Letter continues to provide a compelling link between Jewish history and the broader ancient world.

Why Most Matzah Is Not Kosher for Passover

Ever noticed that most matzah packages are labeled “Not Kosher for Passover” and wondered why? The answer comes down to two key factors: cost and ingredients.

Producing kosher for Passover matzah is a meticulous and costly process. It requires specially milled flour, strict mixing protocols and constant rabbinic supervision. As Rabbi Daniel Senter explains in Streit’s: Matzo and the American Dream, “Generally, when you make production for kosher, if the equipment, process, and ingredients are all kosher, you’ll have a kosher product.

But with Passover matzah production, we’ve got this added component of time: If you mix flour and water together, you’ve got 18 minutes to get it through the system. Otherwise, that dough will become ‘chametz’ (leavened) and not kosher for Passover. If there’s any break in production for more than 10 minutes, we have to start over again.”

The other factor is taste. Over 25% of matzah sales happen outside of Passover, meaning many consumers look for a more flavorful experience. To meet demand, matzah manufacturers offer varieties like egg matzah, “everything” matzah and onion matzah. However, these versions do not meet the strict Passover requirement of being made only with flour and water — making them delicious year-round but not suitable for the holiday. So, next time you see a matzah box labeled “Not Kosher for Passover,” you’ll know it’s either because of the cost and complexity of production — or because someone wanted to make the bread of affliction a little tastier!