The Freedom Seder – A Revolutionary Haggadah

By Casey J. Adler

Today as well, we face Plagues that trouble the earth and all humanity. Who and what are the institutional pharaohs in our time? What are the destructive Plagues of our own generation? What can we do to bring Ten Blessings, Ten Healings, on the earth in our own lifetimes? It is time for a new birth of freedom, time for a NEW FREEDOM SEDER.

— Excerpt from The Freedom Seder, updated in 2014, by Rabbi Arthur Waskow & Arlene Goldbard of the Shalom Center

On Thursday, April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was shot dead at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee — 8 days before he was scheduled to attend a seder at the home of Rabbi Abraham Heschel. Upon hearing about Dr. King’s death, Arthur Waskow, a Washington, D.C. resident, Vietnam activist and future rabbi, began to cry when he explained to his 5-year-old son that “a great man was murdered.”

However, it wasn’t just the assassination of Dr. King that would change the course of Waskow’s life’s work. Rather, it was the reaction of the American government.

Dr. Alissa Schapiro, a curator at the Skirball Museum, explained that as Waskow was leaving his office in Washington, he witnessed the National Guard and U.S. Army brutalizing Black protesters to enforce a curfew, and he realized that the U.S. military was “the modern manifestation of Pharaoh’s army.”

According to Dr. Schapiro, it was this “connection between the Civil Rights Movement and the story about the exodus from bondage that felt as though the Jewish story was understood in the contemporary moment.”

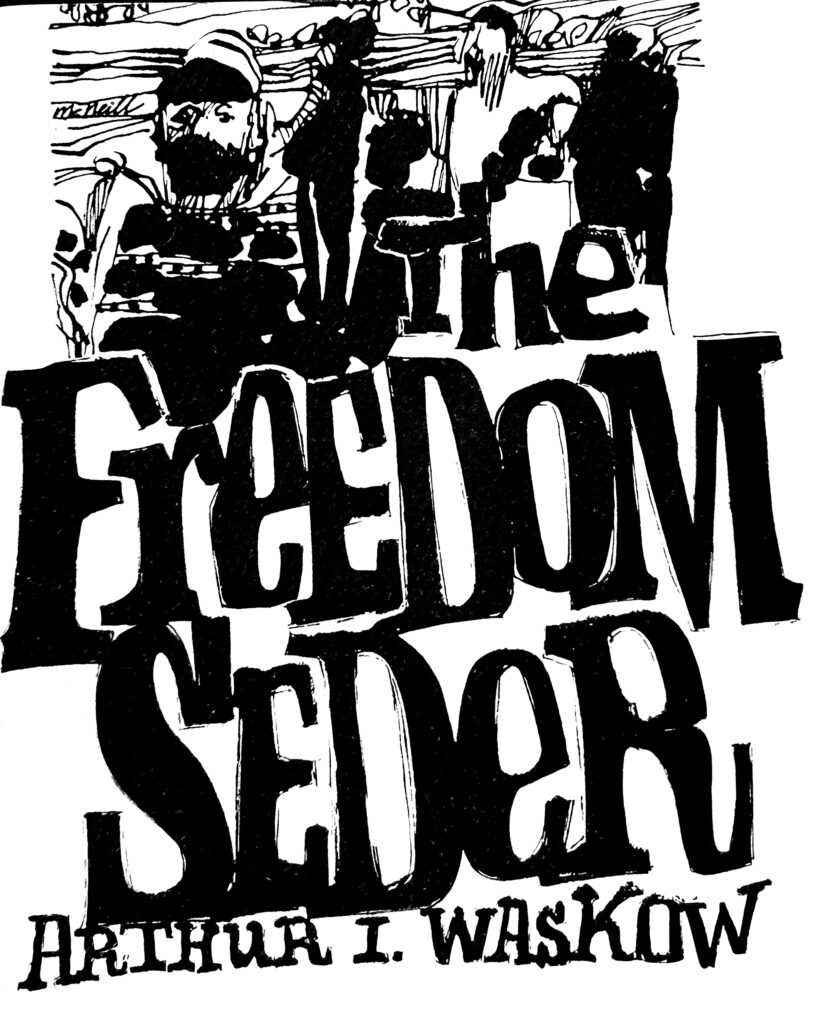

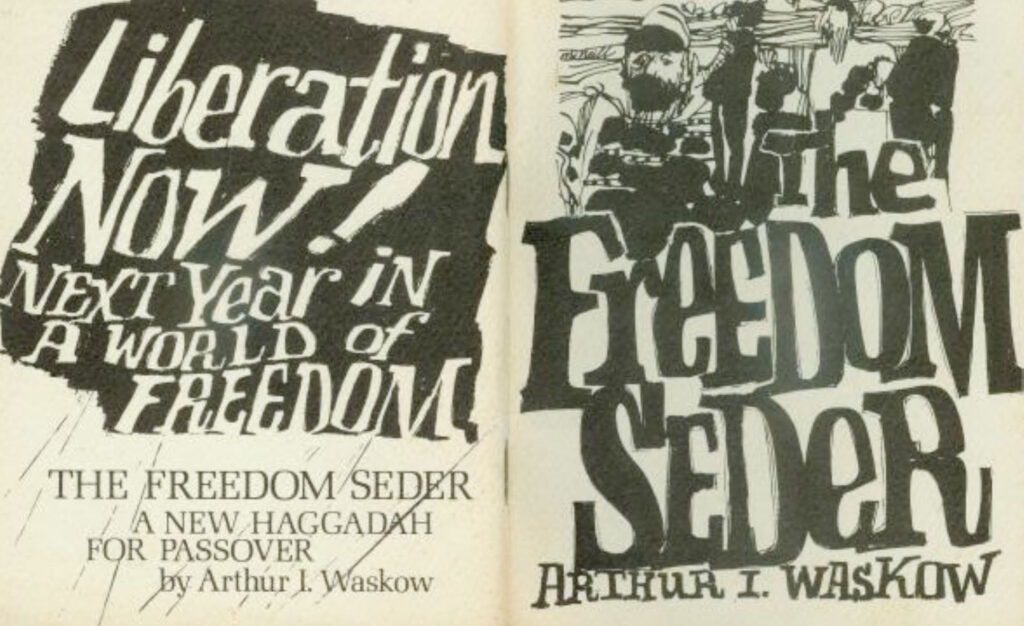

One year later in 1969, Waskow created his own unique Haggadah called “The Freedom Seder” to advocate for a new freedom from the modern plagues — or what Dr. King called the triplet of racism, materialism and militarism.

The first Freedom Seder occurred not in a synagogue or a JCC, but in the basement of Lincoln Temple, a Black church. Eight hundred attendees — Black and white, Jew and Christian — joined in commemorating Passover using Waskow’s Haggadah, which “wove the story of the liberation of ancient Hebrews from Pharaoh with the liberation struggles of black America [and] the Vietnamese people,” as quoted by NPR.

From Waskow’s article, “Why I wrote the Freedom Seder and Why It’s Still Necessary,” he expands, “Where the old Haggadah had what seemed to me a silly argument about how many plagues had really afflicted Egypt, I substituted a serious quandary: Were blood and death a necessary part of liberation, or could the nonviolence of King and Gandhi bring a deeper transformation?”

Dr. Schapiro showed off two of the original publications of The Freedom Seder, which she said came into the Skirball’s possession in 1986, just 17 years after its creation. “You have in the 1970s these other social justice, environmentalist, queer and feminist Haggadot that are coming out, but to have this one in 1969, it is seen as the originator of that concept — launching the tradition of figuring out how to relate the Passover story to contemporary events.”

Examining the Haggadah is a unique experience all on its own, as it is a mixture of Jewish liturgy and ’60s art. Rabbi Waskow asked Lloyd McNeil, a non-Jewish Black D.C. visual artist and jazz musician, if he would illustrate it. Waskow said, “I was clear that I wanted a black artist to join in the Freedom Seder so that it made sense and it wasn’t just an add-on.”

David Chack, a cantor and professor of Holocaust drama at DePaul University, said he encountered his first Freedom Seder in the early ’80s. He partnered with Jewish and Black leaders in the Boston area, just like the original Freedom Seder in 1969, and brought together residents of all races to teach the Passover tradition and have a discussion of the civil rights issues, “We would do it from the perspective of the least advantaged, [before] discussing the plague of slum lords, the plague of defunding schools, and so on.”

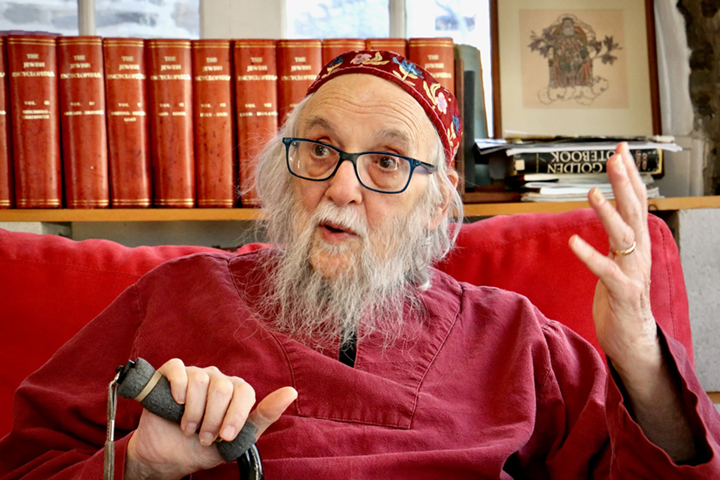

In an interview with Rabbi Waskow, he said that he grew up in the segregated school system of Baltimore. He was the editor of his high school newspaper and recalled an incident in which the vice principal told him, “In my lifetime and in your lifetime, racial segregation won’t end in the Baltimore school system.”

To the radical young mind of Waskow, that was not only ethically wrong, it would also be factually wrong. Throughout the ’60s, he struggled with his fellow Jewish comrades as allies in the support of civil rights. He joined Jews for Urban Justice (JUJ), which advocated for civil rights, including Black tenants being exploited by landlords, Jewish or non-Jewish. According to Tablet Magazine, JUJ was “the first leftist Jewish group of its kind” in the ’60s and ’70s. It was not only anti-racist and anti-war,” it was “often an anti-Jewish establishment … straddling the worlds of radical activism and Jewish community.”

I asked Rabbi Waskow what freedom meant to him in the ’60s and if it had changed. He said, “It has broadened a lot. Now I see if you’re going to be a Pharaoh, you have to smash every group of people who assert that they are entitled to their equality.”

As our discussion moved back to Dr. King’s triplets of racism, materialism and militarism, Rabbi Waskow said, “For years, I asked myself why Dr. King called them triplets — not a ‘trio’ — and what came to me is that triplets have the same DNA, but trios may not. The DNA of racism, materialism and militarism — and, I would add, the fourth being sexism — is greed and subjugation.”

Though Rabbi Waskow’s beliefs may have been considered radical in the 1960s, his passion for non-violence and radical liberation has not abated, even if that means he stands against the mainstream of American and Jewish society. I asked him what he believes are the largest problems Jews face today, and he said, “I think that the massacres of Israel are an ethical stain on Jewish history and Jewish conscience.”

He went on to implore his fellow Jews to act in accordance with the tradition of teshuva and repair the world through tikkun olam. In keeping with his steadfast belief in building community and breaking barriers, the 50th anniversary of The Freedom Seder was held at a Black mosque “to assert the equality of religion and race in American society.”

Building community and opening dialogue were the core phrases echoed by both Professor Chack and Dr. Schapiro in the discussion over The Freedom Seder. Schapiro noted that “it’s not necessarily the Haggadah itself, but it’s the practice of Passover: Who do you celebrate with, who do you share your traditions with, and for me, as someone whose scholarship looks so much on anti-Semitism, the idea of sharing Jewish religious traditions with others who are not like yourself — to show that we share basic core values.”

I asked Rabbi Waskow if he were to recreate The Freedom Seder today, what would some of the plagues represent. He responded, “The decision to exclude immigrants and refugees from American society, the intention to expel millions of foreign-born people, the attempt to squash the social gains of gay people and LGBTQIA from the legal equality that they had won in the ’90s and afterwards, and the attempt to wipe out the right for women to control their own bodies.”

Rabbi Waskow has proven to be a trailblazing and prophetic voice in Jewish and American life for more than half a century, but his power for change has not stopped with age. He continues to write articles, take interviews, and lead events with The Shalom Center, the institution he founded forty years ago. If you are interested in utilizing one of Rabbi Waskow’s Haggadot for Passover, including the original 1969 version, visit Resources at The Shalom Center, which includes a comprehensive library of reimagined resources for the holidays.