What Pasover Teaches Us About Mercy and Goodwill by Rabbi Dr. Morey Schwartz

The spoils of war are far less fulfilling than rewards born out of kindness. Since the inception of Judaism and throughout thousands of years of existence, the Jewish people have benefited most in times of peace and suffer most amid violence. Despite our internal differences, the importance we place on grace and goodwill have kept the Jewish world safe from infighting and greedy conquest that have destroyed countless other nations. As the largest pluralistic Jewish learning platform, the Melton School places unique importance on these values. Navigating the challenges that stem from differences within the Jewish world are a key aspect of my work as international director.

Over countless educational experiences across a breadth of denominations, I have learned firsthand that mercy and goodwill are essential to a fruitful Jewish future. Ahead of Passover, we see that this idea has its roots in Parashat Bo.

There is a long-standing biblical tradition that already at the time of Abraham, the nation of Israel was destined to ultimately be enslaved to a foreign power for hundreds of years. And G-d said to Abram, “Know well that your offspring shall be strangers in a land not theirs, and they shall be enslaved and oppressed four hundred years; but I will execute judgment on the nation they shall serve, and in the end they shall go free with great wealth.” (Gen. 15:13-14)

This verse is actually included in the maggid section of the hagaddah. As we see, just as slavery was anticipated for many years, so was the promise that when it would come to an end, the Israelites would embark upon freedom not as indigents, but with great wealth and riches.

“Mercy and goodwill are essential to a fruitful Jewish future.”

This notion might make us a bit uncomfortable. Was the promise of great wealth meant in some way to serve as a consolation to Abraham? “Yes, Abraham, they will be enslaved for four hundred years, and yes it will be really rough…but no worries, it will all be worth it as they will leave their misery as rich people!”

That promise does not seem to be all that comforting. Is it possible that the wealth was not meant as a consolation prize at all, but as something else?

A possible explanation begins to take shape when the promise is restated, in different words, generations later to Moses at the burning bush:

And I will cause the Egyptians to feel favorably toward this people, so that when you go, you will not go away empty-handed. Each woman shall borrow from her neighbor and the lodger in her house objects of silver and gold, and clothing, and you shall put these on your sons and daughters, thus stripping the Egyptians. (Exodus 3:21-22)

In this passage, it becomes clear that the wealth the Israelites will take with them as they depart Egypt will actually represent something more than a consolation prize. It will demonstrate the feelings that the former enslavers will have about their former slaves; “they will feel favorably toward this people,” promises G-d to Moses.

And how will this play out? Are we talking about an intervention by G-d that manipulates the Egyptians and their attitude? Will G-d actually overpower their freedom of choice and force them to dump the wealth of Egypt into the hands of these former slaves, against their will?

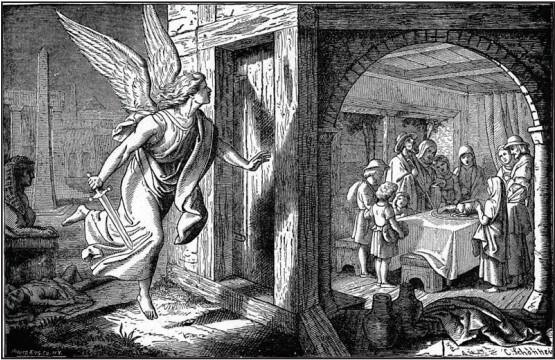

When the event does play out during the night of the Exodus, we gain a profound understanding of what the original promise to Abraham, and subsequent promise to Moses, was really all about. Following the plague of darkness, and before the death of the firstborn Egyptians, G-d tells Moses the time has come to instruct the people to turn to their Egyptian neighbors and take with them the wealth of Egypt:

The LORD disposed the Egyptians favorably toward the people. Moreover, Moses himself was much esteemed in the land of Egypt, among Pharaoh’s courtiers and among the people. (Exodus 11:1-3)

German commentator Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808- 1888) suggests that, in fact, the people had earned the respect of the Egyptians:

The honesty and magnanimity which the Jews displayed during the three days of darkness had so raised the opinion of the Egyptians toward Israel that they pressed their possessions upon them before they asked, and stripped themselves of their treasures.

In other words, though the Israelites could have easily taken advantage of the Egyptians during the previous plague of blinding darkness—for according to the biblical account, the darkness did not affect the Israelites—they did not. This left a strong impression upon the Egyptians, and so they willingly handed over their possessions to the fleeing former slaves.

Polish commentator Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehudah Berlin (1816-1893) addresses verse 3, which speaks of the fondness the Pharaoh’s servants and the Egyptian people felt at this point for Moses:

The servants of Pharaoh had already accepted that Israel was to leave Egypt. And that Pharaoh was hardening his heart without reason. And in any case, they saw Moses hurrying (after the onset of each plague) to pray and show great concern for them. In this way his honor was heightened in the eyes of the Pharaoh’s servants and in the eyes of the Egyptian nation too, even though they were not aware of what was actually said between Pharaoh and Moses.

What both Hirsch and the Berlin teach here helps to explain the nature of that original promise to Abraham and Moses while offering an important lesson for all of our history as a nation. The original promise was not meant to be a consolation prize, a fiscal package or some sort of promised reparations that would be forthcoming to Israelites in compensation for their suffering; rather, G-d promised that when the slavery comes to an end, the nation and its leadership will have earned the respect of their captors. They will go out of their enslavement as much more than a nation of inferior human beings, or a second-rate class of former chattel. They will leave as an envied nation—not only because of the power exhibited by the G-d of Israel who took them out with an outstretched arm, with plagues, signs, and wonders—but because of their choices, their behavior, and the decisions they made to act justly and mercifully without regard for how deserving the Egyptians were of such courtesy.

The Melton School promotes a culture of courtesy and mutual respect to make the most of our shared learning opportunities. When conflicts do arise between learners with contrasting opinions, or staff with differing visions, we remember that respect and reconciliation yield the best outcomes as evidenced by Parashat Bo. Perpetuating bitterness provides no path to such rewards.

As it was then, so may it be always. It is in the face of adversity that we are most challenged as a nation to act according to the ethics and morality for which we stand.