Who’s Who of Hanukkah

You’re probably well-versed on the story of Hanukkah, but how well do you know the people behind the Festival of Lights? Unlike many other Jewish holidays, Hanukkah is not mentioned in the bible.

The story of Hanukkah is recorded in the first and second book of Maccabees, and it was later included in the Talmud. And when it is mentioned in the Talmud, there’s more of a focus on the miracle of the oil that lasted for eight days than the uprising that led to the miracle:

“When the Greeks entered the Sanctuary, they defiled all the oils that were in the Sanctuary by touching them. And when the Hasmonean monarchy overcame them and emerged victorious over them, they searched and found only one cruse of oil that was placed with the seal of the High Priest, undisturbed by the Greeks. And there was sufficient oil there to light the candelabrum for only one day. A miracle occurred and they lit the candelabrum from it for eight days.” (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 21:1b)

The holiday commemorates the victories of the Maccabees over the Seleucid forces, who were fighting to defend their religious beliefs and freedom. But who were the Maccabees? And who was leading the forces they were fighting? Whether you’re looking for a refresher or an introduction, here are the key players from the story of Hanukkah.

Antiochus IV Epiphanes

In comparison to many antagonists in other Jewish holiday stories such as Pharaoh with Passover and Haman with Purim, King Antiochus IV Epiphanes remains comparatively obscure.

Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the third son of Antiochus III the Great, ascended to the Seleucid throne under unusual circumstances in 175 BCE, seizing power after his brother, Seleucus IV Philopator, was assassinated. Seleucus’ son Demetrius I would have been the rightful heir to the throne, but he was being held hostage in Rome at the time and was still very young.

Antiochus took advantage of this instability and garnered the support of the Greek ruling class to begin his time as ruler. After assuming power, he began a pursuit of conquering Egypt, which would increase his kingdom’s size. But first, he needed to stabilize his existing subjects to gain their support. During his time as ruler, Antiochus sought to strengthen the Seleucid Empire through Hellenization — the promotion of Greek culture, language and religion.

Alexander the Great, who was undefeated in battle and led his armies on a series of campaigns during his rule, spread Greek culture and language to the communities he conquered. However, Alexander still allowed varying cultural and religious practices under his rule, while Antiochus did not.

Jewish traditions and religious rites such as circumcision, dietary laws, observing the Sabbath and studying the Torah were outlawed, which some segments of the Jewish elite went along with, while others largely opposed the cultural assimilation.

The Temple in Jerusalem was desecrated, and an altar to Zeus was erected where pigs could be sacrificed. Antiochus also replaced the Temple’s high priest with a puppet priest, and brutal punishments were carried out by the Syrian army if any of Antiochus’ new rules were opposed.

These decrees put in place by Antiochus in 167 BCE were in contrast to past Seleucid rulers who did not seek to persecute or even exterminate religions within their empire. His actions sparked outrage and resistance, directly serving as the catalyst for the Maccabean Revolt.

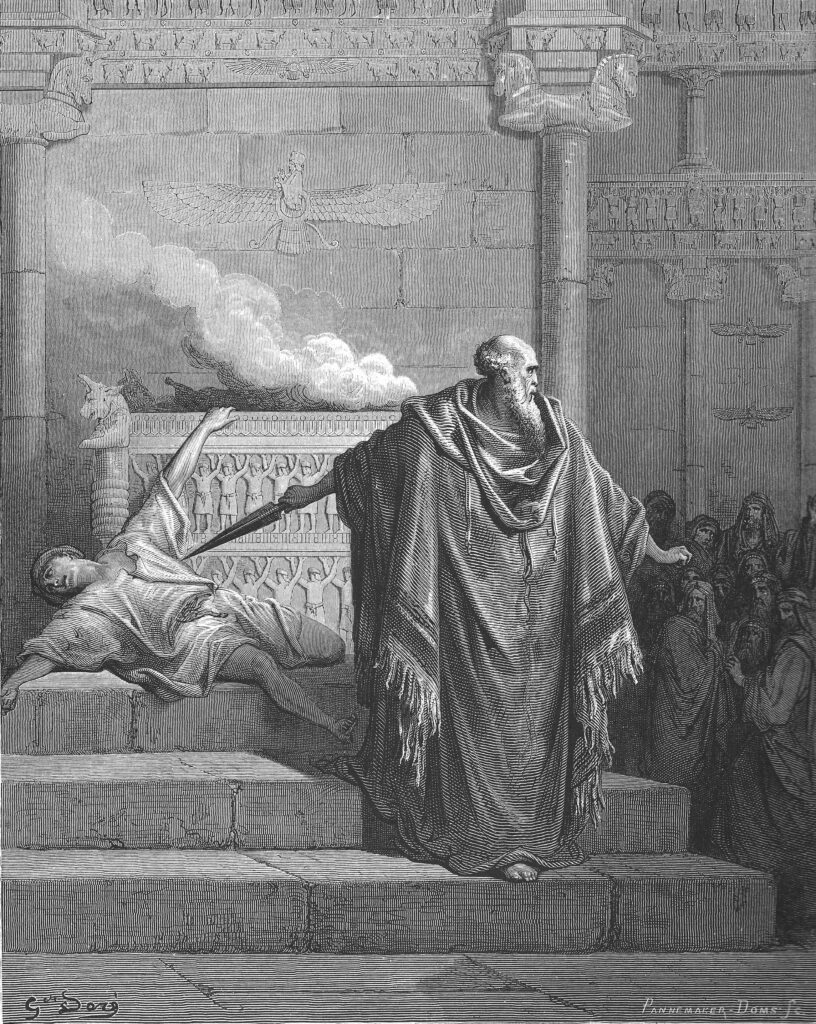

Mattathias

Mattathias ben Johanan, the father of Judah Maccabee, was a devout priest from the village of Modi’in and the initial leader of the Maccabean revolt. In addition to Judah, he had four other sons — Simon Thassi, John Gaddi, Jonathan Apphus and Eleazar Avaran.

When Antiochus IV outlawed Jewish religious practices and demanded that they worship pagan gods, Mattathias refused to conform despite immense pressure on the Jewish community. In 167 BCE, Seleucid officials arrived in Modi’in demanding that Mattathias set an example as a local leader and make a sacrifice to honor a pagan god, but he refused. When another Jew came forward to comply with the sacrifices, Mattathias killed the man as well as the Seleucid officer overseeing the enforcement of the act. With his five sons, Mattathias fled to the wilderness of Judea with rallied supporters: “Then

Mattathias cried out in the town with a loud voice, saying: ‘Let everyone who is zealous for the law and supports the covenant come out with me!’” (1 Maccabees 2:27)

Mattathias led the Maccabees for a year until his death, which occurred sometime between spring 166 BCE and spring 165 BCE, according to 1 Maccabees. Before he died, he assigned his son Judah the role of military commander and his son Simon as counselor.

Though Mattathias did not live to see the revolt’s success, his vision and leadership laid the foundation for victory down the line. His five sons became known as the Maccabees, which translates as “hammers,” a reference to their strength in battle against the Seleucid forces.

Judah Maccabee

Judas (better known as Judah) Maccabeus was the third son of Mattathias. Judah emerged as a charismatic and skilled military leader who took charge of the Maccabean army to defeat the Seleucid forces and regain control of the Temple in Jerusalem. When Mattathias died in 166 BCE, Judah took over the leadership of the Maccabean forces.

Judah’s main strategy was to use guerrilla warfare in the early years of the revolt, but he later organized a more put-together army modeled after the Greek forces. His victories included the Battle of Nahal el-Haramiah, the Battle of Beth-Horon, and the Battle of Emmaus — thanks to the surprise and ambush attacks carried out by the Maccabees.

After the Maccabees gained control of the Temple in Jerusalem in 164 BCE, they cleaned the Temple and found only one flask of pure oil left. It would take eight days to make a new batch of pure oil, but the amount in the uncontaminated flask was only enough for one day. They lit the menorah, which burned for eight days. This miracle and the victory of the Maccabees is commemorated by Hanukkah.

Judah’s work did not stop after the restoration of the Temple in Jerusalem, and he continued to fight with the Maccabean army for Judea’s independence. However, in 160 BCE during the Battle of Elasa, Greek Syrian forces prevailed, resulting in Judah’s death and the defeat of the Maccabees. Despite this, his inspiring leadership laid the groundwork for the Hasmonean dynasty and the future of Jewish autonomy.

Jonathan Apphus

After the death of his brother, Judah, Jonathan Apphus, the youngest son of Mattathias, became the leader of the Jewish resistance. After the death of their father, Jonathan fought in battles against Seleucid forces with his brothers and served under Judah.

In 153 BCE, Jonathan was appointed high priest by Alexander Balas, which helped give him significant religious and political authority over the Jewish people and in Judea. Jonathan made territorial gains in Judea and secured an alliance with the Roman Empire to protect them from additional threats.

Unfortunately, Jonathan’s time as high priest and leader ended in betrayal. In 143 BCE, he was lured into a trap by Diodotus Tryphon, a rival Seleucid general, who captured and executed him. Jonathan was succeeded by his older brother, Simon Thassi, the second son of Mattathias.

Simon Thassi

Simon Thassi, also known as Simon the Great, was the second son of Mattathias and the final leader of the Maccabean Revolt. After the deaths of his younger brothers, Judah and Jonathan, Simon was elected as the leader of the Maccabees in 142 BCE.

Following the work put in by his father and brothers to protect religious freedom, Simon was more focused during his rule on the broader fight for political independence. He negotiated Judea’s independence in 141 BCE with King Demetrius II, which secured self-rule for the Jewish people for the first time in centuries. He expanded the Jewish state’s borders, fortified Jerusalem and officially solidified the Hasmonean dynasty.

In 135 BCE, Simon and his two sons Mattathias and Judah were assassinated by Simon’s son-in-law Ptolemy, a Seleucid governor in Jericho. John Hyrcanus, Simon’s third son, succeeded him as the high priest, and his descendants continued to rule Judea after him.

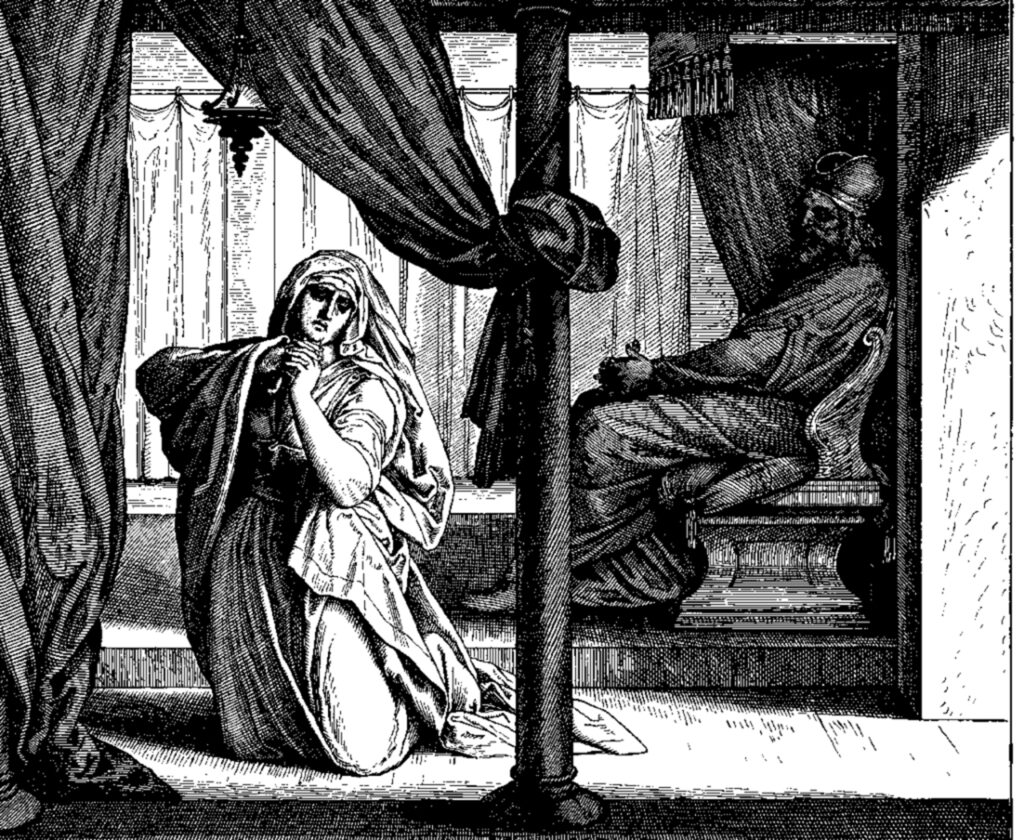

Hannah

While Judah and the other sons of Mattathias are more in the spotlight within the story of Hanukkah, Hannah is not one who should be overlooked.

As her story goes, it was decreed under Seleucid rule the local Greek governor had the right to rape a Jewish woman on her wedding night before she could be with her husband. Because of this, many women chose not to marry. Much like her father refused to sacrifice to honor a pagan god, Hannah refused to submit to this incredibly violating rule. She was engaged to marry Elazar the Hasmonean, and on the night of her wedding feast, she stripped naked in an act of defiance.

Her brothers wanted to kill her for her brazen act, but she was quick to expose their hypocrisy. She spoke out against them, asking how they would be angry at her defiant act but not upset that she was to be raped after getting married:

“Hear me, my brothers and uncles. Yes, now I stand before the righteous naked, without transgression, and yet you are zealous against me. Why are you not zealous against handing me over to the gentile who will violate me? If only you would learn from Simeon and Levi, the brothers of Dinah (and there were only two of them). They were zealous for their sister. And you, you are five brothers — Yehuda, Yohanan, Yonatan, Shimon and Elazar — and more than two hundred youthful priests. Place your trust in God and He will help you!” (1 Sam. 14:6)

Hannah’s brothers dressed her in royal clothing and presented her to the Greek governor, but when they entered the governor’s chamber, a battle ensued, and they killed him.

So as you celebrate Hanukkah this year and in years to come, think of the miracle, yes, but also of the people who fought for it and for the Jewish people.