Purim Through the Ages

Throughout history, Purim has been at the top of fun Jewish Holidays. We get to dress up, party, watch the Purim schpiel, make noise and then feast! The Book of Esther tells us a story from Persia in the Fifth Century B.C. It’s a story of bravery, deception, and triumph over adversity as Esther saves the Jews from Haman’s plan to kill them all. The story starts with the King hosting a 180-day party showing off his empire’s goods and ends with the order to remember the saving of the Jews on the fourteenth day of the month of Adar by having “a day of gladness and feasting, and a good day, and of sending portions to one another.” Jews have been reading the “whole megillah” for years and there are plenty of stories and traditions that have been passed down through the generations.

Roman Law

Going back to the Roman times, on May 29th, 408 CE, Jews were banned from burning Haman in effigy. According to historian Amnon Linder, there are around 107 imperial Roman laws concerning the Jewish population and there is the only one about Purim. The Romans were concerned that the Purim parties would be celebrated to mock Christianity. At that time Haman’s effigy would have been created with Haman on a wooden cross, which could be taken for Jesus. The edict became inscribed in the Theodosian code in 438: Emperors Honorius and Theodosius Augustuses to Anthemius, praetorian prefect. The governors of the provinces shall prohibit the Jews from setting fire to Haman in memory of his past punishment, in a certain ceremony of their festival, and from burning with sacrilegious intent a form made to resemble the holy Cross in contempt of the Christian faith, lest they introduce the sign of our faith into their places, and they shall restrain their rites from ridiculing the Christian law, for they are bound to lose what had been permitted them till now unless they abstain from those matters which are forbidden. Given the fourth day before the calends of June at Constantinople, in the consulate of Bassus and Philippus.

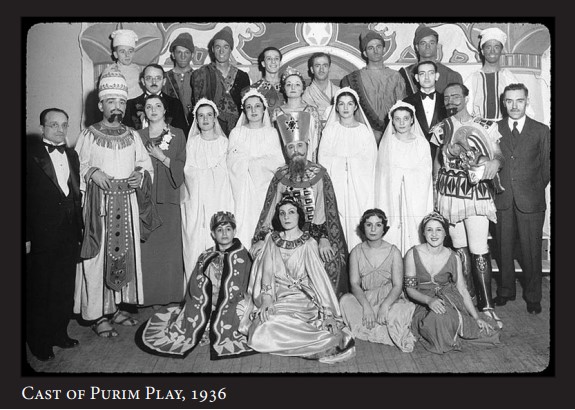

The Purim Spiel

While public enactments of the hanging and burning of Haman go back to Roman times, the Purim Spiel’s got its start in the 1400s. The term Purim-shpil was widespread among Ashkenazi with the first written record found in Venice in 1555 written by a Polish Jew. At first the spiel was often a monologue performed in costume with rhymed phrases from the Book of Esther. Over the years, casts grew from one or a few yeshiva students to include professional entertainers. Groups of touring people called “Spielers” would go from home to home performing and often asking for payment. One of the epilogues from this time period is: “Today Purim has come in, tomorrow it goes out. Give me then my single groschen and kindly throw me out!…” While spiels recounted biblical stories they often made fun of contemporary Jewish life. Beyond satire the acts were often rife with erotic profanity and obscenity. Due to their vulgarity the government in Frankfurt burned a printed version of the Achashverosh Shpiel in 1697 and in 1728, Hamburg’ s government banned the the spiels entirely. Today’s spiels more closely resemble the spiels of the 1800 when larger casts and music often were performed in public places or at a synagogue.

The Grogger

On the shabbat before Purim we read the Shabbat Zachor that says, “You shall blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven” which amazingly has led us to use groggers on Purim. Agag was the king of Amalek during the reign of King Saul and Haman was a descendant of Agag. So, when we celebrate Purim, we must erase Haman’s name and we make noise to obscure his name or literally wipe his name off of the earth. According to the Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) Rabbis’ interpreted the decree and “introduced the custom of writing the name of Haman, the offspring of Amalek, on two smooth stones and of knocking or rubbing them constantly until the name was blotted out. Ultimately, however, the stones fell into disuse, the knocking alone remaining.” There is also a tradition of writing Haman’s name on the bottom of one’s shoes or on the ground. Whenever Haman’s name was mentioned, people would stomp their feet to get rid of Haman making both noise and obscuring the writing. So what about the groggers? Groggers can be found back in Ancient Greece, and survived into the middle ages. As Scholar David Zvi Kalman explains, groggers were used as part of the ceremony called the Burning of Judas, when church bells are silenced. Part of the ceremony included the burning of an effigy of Judas while children rang their ratttles in celebration. Kalman concludes that the Jews appropriated the rattle representing violence and used them to help to destroy Haman’s name. And that’s why we wave groggers today.

Put on a costume, have a Purim cocktail, enjoy some hamentashen. After all, they tried to kill us, we won, lets eat!